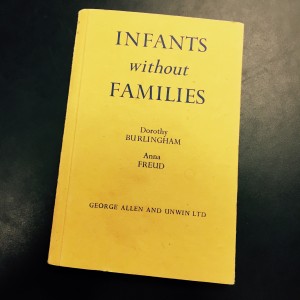

In 1944, Anna Freud and her colleague Dorothy T. Burlingham wrote a book entitled Infants Without Families. This book shared observations from Freud and Burlingham based on their educational work in the three houses of the Hampstead Nursery.” In the foreword of the book, the authors detail for us the context of their work:

“War conditions, i.e., the father’s service in the Forces, full-time factory work of many mothers, evacuation as a precautionary measure and the destruction of many small homes through bombing have disrupted family life among large sections of the population. Consequently many infants, though not parent-less, were rendered homeless. They had to be collected in residential nurseries and there suffered the experience of “life without the family” which is, in peace-time, reserved for the inhabitants of orphanages.

The effect, not merely of the shock of being separated from the family, but of the lack of continuous emotional contact between the infant and his parents with the consequent absence of the specific formative influence inherent in the family tie, was thus open to view in many more than usual and seemed to us worthy of study and description.”

Last week, I explored Bowlby’s concept of parents as a secure base providing safety, security, and protection. Anna Freud saw firsthand the results of interrupted attachments wherein children did not have that secure base. She writes:

“These institutional children do not start out to meet a world of contemporaries, secure in the feeling that they are firmly attached to one “mother person” to whom they can revert. They live in an “age group” that is, in a dangerous world, peopled by individuals who are as unsocial and as unrestrained as they themselves are.” (pg. 23)

Early instinctive wishes have to be taken seriously, not because their fulfillment or refusal causes momentary happiness or unhappiness but because they are the moving powers which urge the child’s development from primitive self-interest and self-indulgence towards an attachment and consequently towards adaptation to the grown-up world . . . (pg. 82)

Freud, like Bowlby also understand that attachment is not just about the mother-child bond. Fathers, she said, have an important part to play:

It is the father’s role, even more so than the mother’s, to impersonate for the growing infant the restrictive demands inherent in the code of every civilized society. (pg. 87)

Finally, in a paragraph that could easily be written today regarding the current challenges in our foster care system, we read:

“If these [attachment] relationships are deep and lasting, the residential child will take the usual course of development….and become an independent moral and social being. If the grown-ups of the nursery remain remote and impersonal figures, or if, as happens in some nurseries, they change so often that no permanent attachment is effected at all, institutional education will fail…The children, through the force of inner circumstances, will then show defects in their character-development, their adaptation to society may remain on a superficial level, and their future be exposed to the danger of all kinds of dissocial development.” (pg. 106)

Attachment bonds are at the heart of relationship and what let us latch on to the love that leads to our development as human beings. It is the family that is naturally the home of this attachment and this is why the family unit is seen as the building block of civil society. Attachment theory, then, is as much about the potential for humans to flourish as it is about child-rearing.