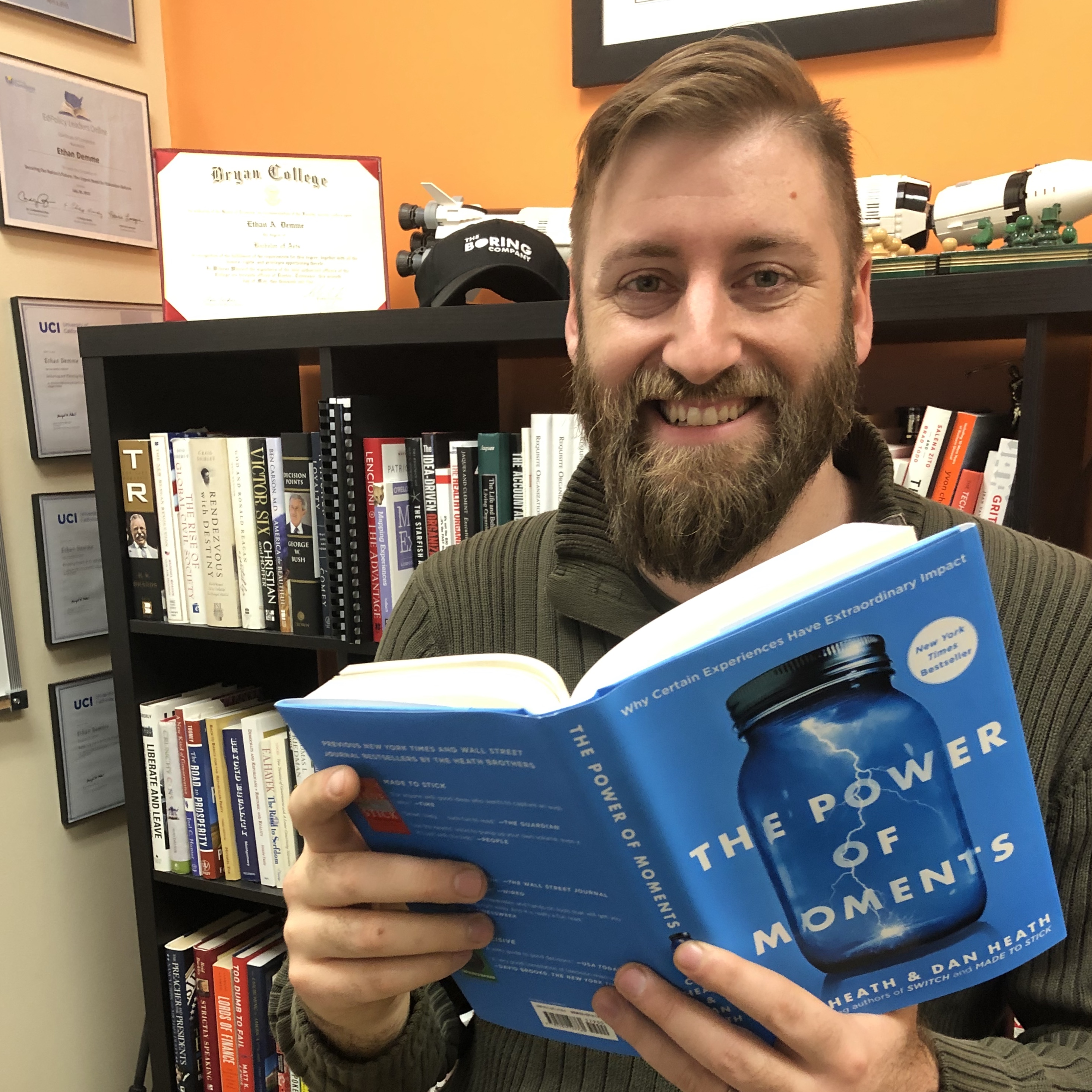

The existentialist philosopher Kierkegaard once wrote that we live forward but understand backward. In their book The Power of Moments, authors Chip Heath (Stanford) and Dan Heath (Duke) help us explore those defining moments in our lives that shape our core identity. The authors identify four main characteristics of defining moments (though some of the most memorable combine two or more of these elements):

Elevation: “defining moments rise above the everyday. They provoke not just transient happiness, like laughing at a friend’s joke, but memorable delight.â€

Insight: “defining moments rewire our understanding of ourselves or the world.â€

Pride: “defining moments capture us at our best – moments of achievement, moments of courage.â€

Connection: “defining moments are social…these moments are strengthened because we share them with others.â€

The authors divide these defining moments into three main categories:

Transitions: promotions, the first day of school, the end of projects, etc.

Milestones: retirement, unheralded achievements, etc.

Pits: dealing with negative feedback, loss of loved ones, etc.

In business as in personal life, the authors argue that we benefit from building the habit of “moment-spotting.†This can often be a harder task in business because we get “consumed with goals†and when that happens “time is meaningful only insofar as it clarifies or measures our goals. The goal is the thing.†But the authors seek to push back against this goal-oriented framework: they remind us that “for an individual human being, moments are the thing.†And they point out that even celebrating an achievement is “embedded in a moment.â€

As an example of concrete defining moments in the workplace, the authors ask us to think about the first day at a new job. “For new employees, it’s three big transitions at once: intellectual (new work), social (new people), and environmental (new place.)†If we can recognize that this first day provides an opportunity for a defining moment filled with elevation, insight, pride, and connection, then we will realize that “the first day shouldn’t be a set of bureaucratic activities on a checklist. It should be a peak moment.â€

In addition to tips on how to recognize defining moments, the book gives helpful advice for how to craft those moments. This advice is often deeply practical and simple, such as boosting sensory pleasures (color, taste, music), but the advice also relies on psychology in suggesting ideas like using games or competition to simulate the feeling that the stakes are raised, or using novelty to challenge expectations and break social scripts.

The authors conclude their book with a series of imaginative what-if questions:

- What if every organization in the world offered new employees an unforgettable first-day experience?

- What if every student had an academic experience as memorable as prom?

- What if every patient was asked, ‘what matters to you?’

- What if you called that old friend right now and finally made that road trip happen?

- What if we didn’t just remember the defining moments of our lives but made them?

This book reminded me of Pixar’s animated movie Inside Out. In this imaginative movie, we see inside the brain command center of a girl named Riley, and we watch as her personified emotions help her to navigate daily life. Inside the ecosystem that is Riley’s brain, we see islands that represent Core Memories – defining moments from Riley’s life.

In my review of the movie, I suggested to parents that you talk to your own children about their core memories: ask your kids about the memories that define them. Ask questions like, “what is your favorite family memory?â€, and “Do you remember what made you feel the saddest?†– Let your children take the lead because the memories that are core to them may not be what you’d expect . . . but don’t be afraid to use prompts as need, i.e., “remember when we first got Rover?†As we enter into this New Year, reflecting as a family on defining moments, both individual and familial, can help contextualize those resolutions and goals we have set for 2019, while helping us avoid being consumed by those goals and instead remain watchful for those extraordinary moments that enrich life.