Few people have had as dramatic an influence on modern ideas of child education as Maria Montessori. Born in 1870, Montessori was an Italian physician and educator. Maria drew on her own experiences working with children as well as insights from her Roman Catholic faith to pioneer a new way to help children learn. Her approach, known as the Montessori method, continues to be used with great success today.

In the preface to Maria Montessori’s treatise on childhood learning The Secret of Childhood, Maria’s son Mario clearly articulates the vision that his mother shared. In the first words of this preface, he writes:

“Today’s problems with regard to youth and childhood are the most patent proof that teaching is not the most important part of education. Yet the delusion persists that adults form the man through their teaching of the child.”

Montessori begins her book exploring the roots of child psychology. She shares some gleanings from psychoanalytic theory but is quick to mention the limits of Freudian psychology, writing that “it was from treating the sick that Freud deduced his psychological theories. The new psychology was, as a consequence, largely based on personal experiences in dealing with abnormal cases. Freud beheld the ocean, but he did not explore it, and he portrayed it as a stormy strait.”

At the center of the Montessori way is an understanding of the child as a person worthy of respect. She writes, “I have come to appreciate the fact that children have a deep sense of personal dignity. Adults, as a rule, have no concept of how easily they are wounded and oppressed.” (pg. 126-127)

Of course, it is equally true that a child, while a person, is still at the beginning of their journey of development, a journey that unfolds over the whole human life span. It is in childhood that personality begins to develop and reveal itself. Maria calls this a “secret work of ‘incarnation” and comments that “the child is an enigma. All that we know is that he has the highest potentialities, but we do not know what he will be. He must ‘become incarnate’ with the help of his own will.” (pg. 32)

After laying the pedagogical foundation in Part 1, Montessori moves on to the education of the child in part 2. Here, what stands out to me, is two key insights:

1. Repetition of exercise. Activities where the child is completely absorbed in an activity that is repeated over and over (like stacking and unstacking cups.) Montessori found this to be a natural part of the way children explore, learn, and grow.

2. Free Choice. This is what we might call student-directed exploration. Montessori understood that while external rewards rarely are effective motivators for learning, autonomy in exploration taps into the child’s intrinsic sense of joy in learning.

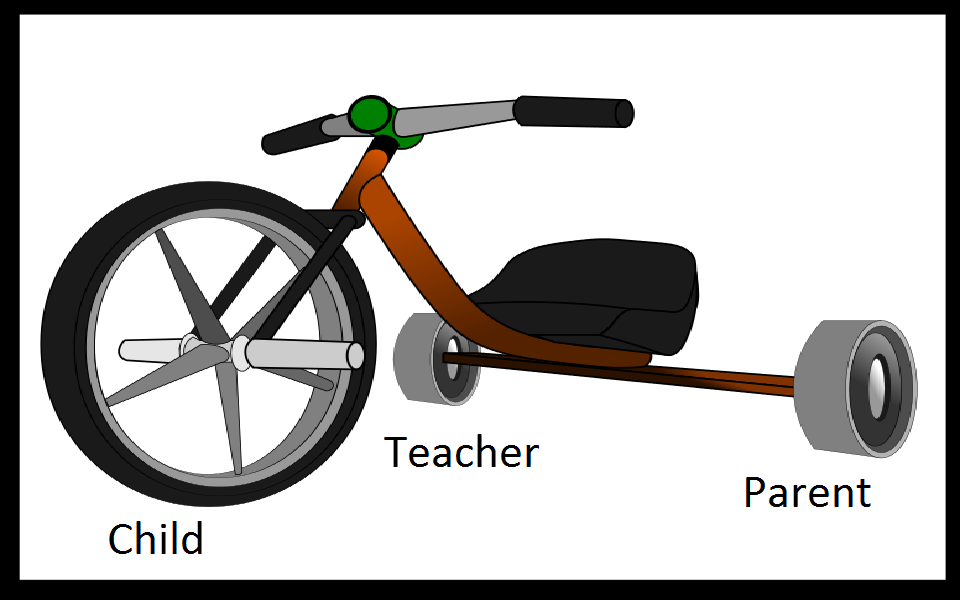

Towards the end of the book, Montessori turns attention on teachers/parents. In order to be effective in teaching children, Montessori writes, adults must prepare themselves through self-examination and reflection on their inherent weaknesses and vices. In particular, adults must specifically address their own anger and pride because these two vices will subvert the efforts of an adult to teach a child.

Did you know that the founders of Google attribute their success to their Montessori education? Watch the short 1.5 minute video below to hear their interview.

Montessori’s insights along with the pioneering work of Anna Freud and John Bowlby build a clearer picture of how children develop, attach and learn.

Click here to read my book review of John Bowlby’s A Secure Base

Click here to read my review of Anna Freud’s Infants Without Families